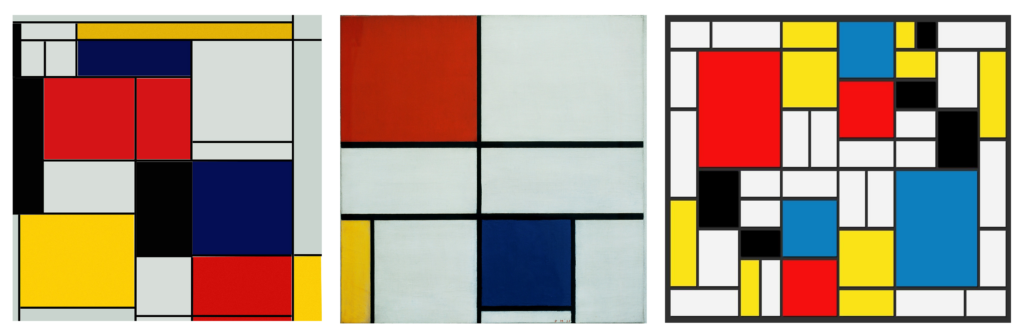

Piet Mondrian’s works have long been celebrated as pioneering exercises in abstraction, distilling the world into grids and primary colours. But what if these seemingly minimalist compositions are, in fact, intricate codes—blueprints for metaphysical realities? Looking at Mondrian through the same lens as Malevich and Rothko, we begin to see that his geometric precision wasn’t just about aesthetics—it was about mapping the unseen forces that shape reality.

The Hidden Symbolism in Mondrian’s Grid

Mondrian was deeply influenced by Theosophy, an esoteric movement that sought to uncover universal spiritual truths through geometry, colour, and mathematical harmony. His transition from naturalistic landscapes to pure abstraction wasn’t just an artistic evolution; it was a deliberate process of distillation, revealing a hidden order beneath the material world.

Key elements to consider:

- The Grid: More than a design choice, the intersecting vertical and horizontal lines create M-shaped junctions, which could represent the meeting of different planes of reality—material (horizontal) and spiritual (vertical). These intersections suggest points of transformation or enlightenment.

- The Colours: Mondrian’s strict use of primary colours aligns with Theosophical teachings about fundamental cosmic forces:

- Red – The material world, physical energy, passion

- Blue – Spiritual elevation, higher consciousness

- Yellow – Intellectual enlightenment, illumination

- White – Pure potential, the divine void

- Black – Boundaries between states of existence, hidden structures

- Asymmetry and Balance: His compositions, while appearing simple, are based on complex mathematical ratios. These relationships might encode numerical harmonies akin to sacred geometry, mapping out the vibrational frequencies of reality.

Mondrian’s Work as a Visual Theology

Instead of portraying traditional religious iconography, Mondrian may have embedded metaphysical principles into his compositions. The careful placement of colours and lines suggests an encoded spiritual system—a visual theology—that operates like a language for those attuned to it.

Consider his Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow (1930)—the famous piece now synonymous with modernist design and even L’Oréal branding. If this work is an encoded spiritual map:

- The grid is not just structure—it’s a cosmic framework, a representation of order imposed upon the chaos of existence.

- The colour blocks are not randomly placed; they could signify energy fields interacting, portals into different aspects of reality.

- The white space is not emptiness but pure potential, the unseen fabric of existence.

The Irony of Mondrian’s Commercialization

One of the most striking aspects of Mondrian’s legacy is how his work—potentially an esoteric code—has been stripped of meaning and turned into a corporate aesthetic. His grid-based compositions now appear on fashion, cosmetics, furniture—reducing his complex metaphysical investigations to mere decorative patterns.

This mirrors what happened with Malevich and Rothko, where deep spiritual or political undertones have been overlooked in Favor of surface-level appreciation. It raises an interesting question: Was Mondrian’s work always meant to be hidden in plain sight?

Mondrian’s Evolution: From Nature to the Divine Blueprint

Mondrian’s early career included landscapes—actual trees, rivers, and fields—before he moved toward the rigid geometry of Neo-Plasticism. But if we look closer, even his early works are already deconstructing reality into hidden patterns. His famous Gray Tree (1911) hints at the grids to come, with branches nearly abstracted into intersecting lines.

His late works, like Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942-43), appear to depict the energy of city life, but they also suggest an evolved mapping of dynamic spiritual forces—a culmination of his system, not just a stylistic shift.

The Rothko Connection: Standing Inside the Code

Rothko insisted viewers stand inches away from his canvases to be overwhelmed by their scale and colour vibration. Mondrian, in contrast, requires distance—the compositions demand a detached, almost meditative engagement. This could reflect different aims: Rothko sought immersion in raw experience, while Mondrian provided a structured system to contemplate.

But both artists were interested in direct spiritual engagement beyond religious constructs. If Rothko’s works were portals of emotional transcendence, Mondrian’s might have been cosmic schematics, teaching the viewer how to perceive deeper structures of reality.

Mondrian’s Work as a Visual Operating System

If we accept that Mondrian was encoding a metaphysical system into his paintings, it reframes his work entirely. His grids aren’t just exercises in balance but maps of energy fields. His use of colour isn’t just aesthetic—it’s symbolic of vibrational states. His seemingly rigid structures are actually pulsating with hidden order.

Perhaps the biggest realization is that Mondrian’s work doesn’t just depict something—it functions as an operating system for perception. If you understand the code, you can use it.

The question is: was Mondrian simply experimenting, or was he leaving behind a toolset for future understanding?

And if so, who was meant to decipher it?