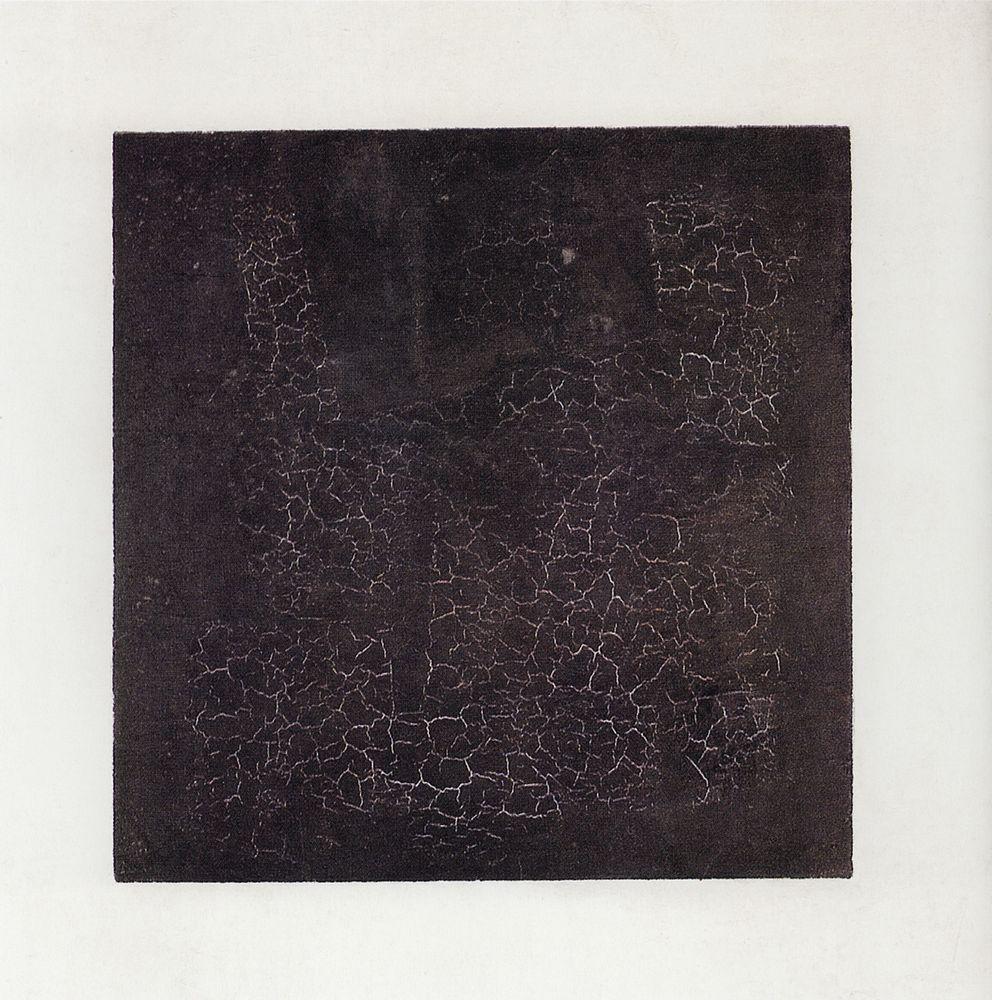

In the vast landscape of modern art, few pieces provoke as much debate, interpretation, and outright existential puzzlement as Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square. It is the kind of artwork that appears to say nothing and yet might say everything. But what if Black Square is more than an exercise in abstraction? What if its purpose was not only artistic revolution but a concealed critique of theological and societal structures? Could its seemingly simplistic presence be an esoteric cipher, disguised as a minimalist statement?

The Black Square: Saturn’s Mark on the Canvas

If we consider Black Square as more than a visual declaration of Suprematism, we can trace an interesting series of alignments. The black square as a symbol recurs throughout religious and esoteric traditions: the Kaaba in Mecca, the Jewish tefillin, the Masonic checkerboard. More intriguingly, black is often linked to Saturn, the planet of structure, time, and material reality.

Saturn’s association with control, limitation, and the harsh nature of existence suggests a powerful reading: Black Square could be a representation of the rigid structures imposed upon human consciousness by religion, dogma, and social order. Malevich, in encoding these ideas, may have produced the ultimate visual paradox—a shape that both represents authority and the void beyond it.

A Cohesive Metaphysical System?

A deeper analysis of Malevich’s Suprematist works suggests that they were not random experiments in abstraction but part of a unified symbolic language. His key geometric forms, all unveiled together at the “0.10” exhibition in 1915, represent distinct cosmic principles:

- Black Square – Material limitations, Saturnian constraints, the structured earthly realm

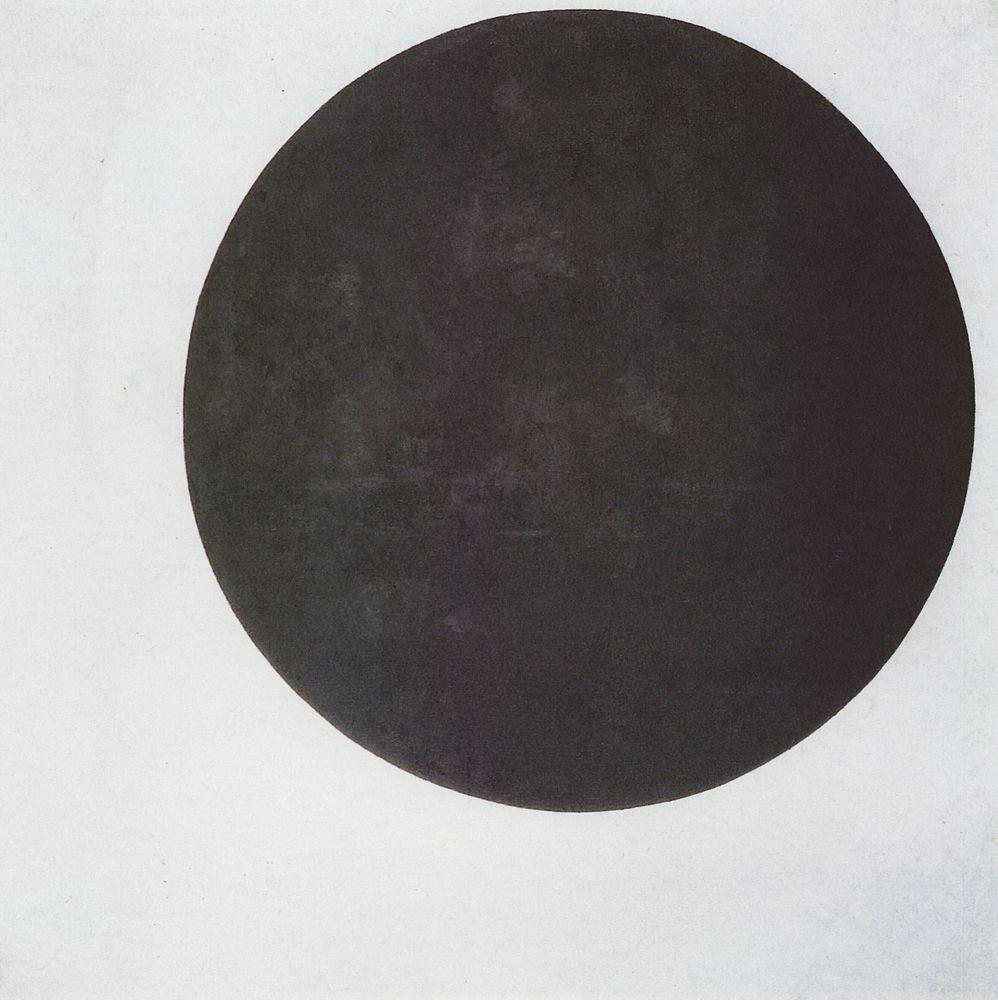

- Black Circle – Cosmic unity, infinity, pure boundless energy

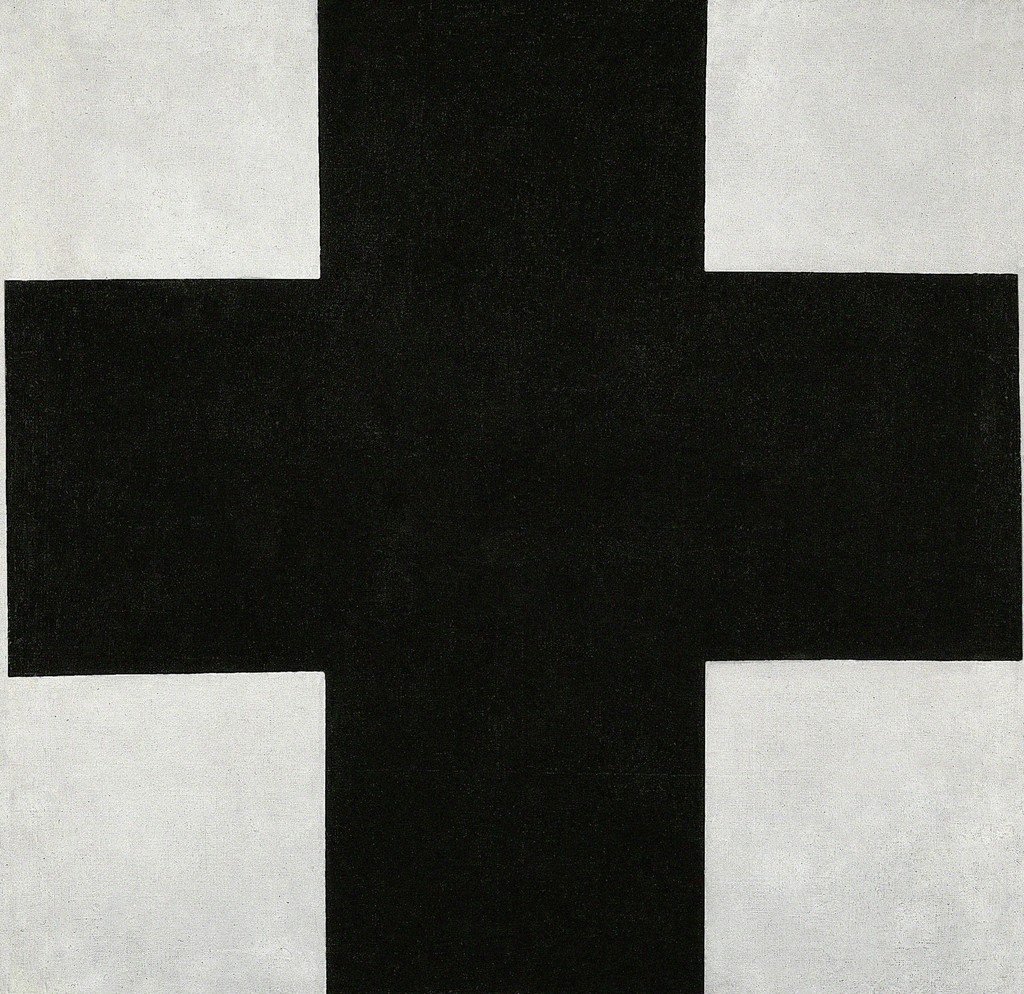

- Black Cross – The division of realms, structure imposed on spiritual experience

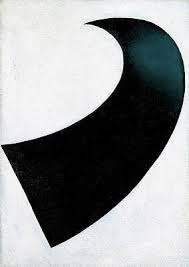

- Black Crescent – Transformation, partial revelation, the square “unfurling” itself

Interestingly, the Black Square was placed high in the corner of the exhibition space—where Russian Orthodox icons traditionally hang. This positioning could suggest an intentional challenge to religious structures.

The Not-So-Square Square

An artist of Malevich’s intelligence and precision would not simply create a shape without meaning, and yet, Black Square is not actually a perfect square. This imperfection could signify the inherent flaws in the ideological structures it critiques. Religion, power, and human institutions strive for rigid control, yet they are inherently “wonky”—inconsistent, contradictory, and ultimately unstable. Black Square may not just be a geometric statement, but a deliberate critique on the fallibility of human attempts to impose divine perfection on the material world.

A Progression: From Black to White

Malevich did not stop at Black Square. He continued his exploration through Black Cross, Black Circle, and eventually White on White. If Black Square represents material restriction, then White on White might signify the transcendence beyond it. A structured sequence emerges:

- Black Square: The material world, restriction, control (Saturnian limitations, religious dogma)

- Black Cross: The intersection of human essence with institutional force (sacrifice, division)

- Black Circle: The containment of cosmic cycles and the divine within rigid structures

- Black Crescent: The unfolding of structure, revealing its own limitations

- White on White: The ultimate transcendence, escaping all imposed forms

What appears at first to be a radical break from tradition may actually be an encoded roadmap—a transition from control to liberation.

The Rodchenko Response: From Subtle to Violent

Fast forward nearly a decade, and Alexander Rodchenko’s work begins to aggressively build upon Malevich’s geometric language. In particular, his Books poster (1924) seems to push Malevich’s quiet subversion into a realm of violent imposition. The geometries have shifted:

- The circle is no longer quietly intersected—it is now forcefully pierced.

- The black square has unfurled into a dynamic form, no longer static but consuming itself.

- The red, once confined within Malevich’s forms, now dominates the space aggressively.

If Black Square was a warning, Books could be its fulfilment: “You wanted revolution? Now see what happens when structures dissolve, only to be replaced by new ones.” The aggression in Rodchenko’s geometry suggests an unintended consequence of Malevich’s vision—control does not vanish; it merely changes hands.

Geometry as Hidden Language

By analysing Malevich and Rodchenko through this lens, a compelling pattern emerges. The rigid containment of form in Black Square gives way to the frenetic, almost violent interventions in Rodchenko’s compositions. The geometric language suggests that power structures do not disappear—they shift, morph, and reassert themselves under new symbols.

If we follow this hypothetical thread, then Malevich’s work is not just the birth of abstraction—it is a deeply encoded critique of human civilization’s need to organize, constrain, and ultimately consume itself. His wonky, imperfect square may be the most honest artistic statement ever made: control is an illusion, and every rigid structure is already in the process of unravelling.

The Disguise in Plain Sight

At the end of our journey through Malevich’s black geometry, one thing becomes clear: Black Square is a masterpiece of disguise. Malevich encoded within it a critique of power, structure, and spiritual control. By reducing everything to its simplest form, he might have revealed the most profound truth of all—that the systems we take as absolute are as fragile as the brushstrokes that form them.